- Home

- Rochie Pinson

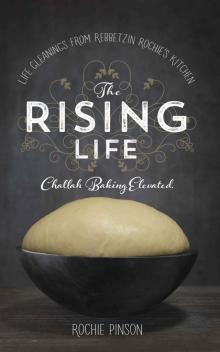

The Rising Life Page 3

The Rising Life Read online

Page 3

a closed square, while the word challah ends with the letter Hei,

which is open on its left side and bottom.

The story of the world’s creation is one of speech: “G-d spoke

and it came into being” (Tehillim 33:9). Each letter of the Hebrew

alphabet, therefore, presents us with worlds of meaning.

In the story of letters and words being the tools of creation,

the four letters of the Tetragrammaton, the name of G-d that

represents His infinite potential and light, play an all-important

role. They are the letters through which Divine energy constant-

ly flows into this world, creating it anew at each moment. One of

these four letters, the letter Hei, is the letter of both giving and

receiving. The Hei has a perfect flow. It receives from above and

then, in turn, gives to below. And this cycle is continuous and

perfect.

This Hei in the flow of creation is the same Hei as in the word

challah, transforming it from ordinary lechem into extraordi-

nary challah. Challah may look like bread but it is really so much

more than that. Challah is baked in large batches, always served

in pairs, and is never just about our own personal survival. The

very word challah, which comes from the Torah in the directive

to separate the first of our dough as a gift, indicates that this

loaf is selected and sacred. When we take off a small piece of the

dough and declare it to be the separated challah gift, we are tes-

tifying to the fact that we are aware of a larger reality, something

bigger than ourselves and our own physical needs.

3 1

R I S I N G

Transcendence in Our Tents

When our Holy Temple stood, challah was gifted to the priests

who served without thought of their own sustenance and there-

fore required the gifts of others. The Torah, however, speaks of

the challah being a gift for the future, as well, preparing us for

a time when there would be no Temple, no priest, and, yet, the

challah would be as relevant as ever.

During Temple times, spirituality seemed to be something

lived outside of one’s self. The Temple was an address for holi-

ness, the priest was the person who represented the Divine here

on Earth and, in order to achieve connection, a person would

travel outside of his or her home to another place.

With the destruction of the Holy Temple and this way of life,

our awareness of spirituality and how we were to achieve con-

nection needed to experience a shift. When we no longer had a

Temple to travel to nor a priest to turn to, we became compelled

to turn inward and find that we ourselves are priests, our own

homes holy temples, and that the greatest connectivity possible

is always right here, within our hearts and minds.

Infinite Awareness

This awareness that our physical space and actions are the ul-

timate breeding ground for deep spiritual connection is a reality

that was first recognized by women, as is evidenced throughout

our storied history.

We learn of our foremother Sarah’s tent as a place of life-sus-

taining miracles: the Cloud of Glory that rested above it, the

3 2

T H E G I F T O F C H A L L A H

candles that remained constantly lit within it, and the bread she

baked, which never grew stale.

These miracles are indicative of Sarah’s life experience. She

lived with a constant awareness of the world of spirit while cul-

tivating her physical surroundings: In her relationship with her

husband, there was a “Cloud of Glory” that rested above, indicat-

ing the presence of the Shechinah, the feminine aspect of Divine

that rests in a place of perfect harmony. In her surroundings, the

small confines of her open tent, she created a place of beauty,

the ever-burning candles representative of a physical grace that

transcends its earthly reality and becomes something endlessly

alive. In her nurturing of her family, the bread she baked to feed

them was infused with a love and care for their spiritual wellbe-

ing as well as their physical bodies. As such, this bread became

transcendent of its earthly properties and did not “die” as phys-

ical things do, yet stayed fresh and alive from baking to baking.

Such is our power as women: to nurture others in a way that

is much more than just the physical feeding and caring of them.

Through our awareness of a transcendent reality, we connect

the ones we love to the Source of life and love that is beyond the

material world and raise them to recognize themselves as more

than physical bodies, mere collections of matter, but as G-dly,

elevated beings—including, as ever, ourselves in this transfor-

mation. The practice of baking challah and the separation of the

“challah gift” are our gateways into this awareness.

3 3

R I S I N G

“Boi Kallah Shabbat Malkata”

ENTER, OH BRIDE, THE SHABBAT QUEEN

— Rabbi Shlomo HaLevi Alkabetz

(C. 5260-5340)

3 4

Chapter II

Shabbat, Challah & Woman

: Three of a kind

“Boi Kallah Shabbat Malkata”

ENTER, OH BRIDE, THE SHABBAT QUEEN

3 5

R I S I N G

Shabbat observed in its fullness is something, much like sleeping

and eating, that we have to get to adulthood to fully appreciate.

When my children were little, I made sure to hoard all spe-

cial treats for Shabbat, creating an excuse for them to crave the

sweetness of the day. It has been a tremendous source of nach-

at for me to watch my children grow to delight in the inherent

sanctity of the day of Shabbat, although the addition of a great

dessert never hurts, either!

As I light the candles on Friday evening, the sky outside is

painted in a wash of soft pinks and lavenders and an incredible

feeling of relief rushes over me. There is nothing left to be done.

All of creation is perfect right now. And, for the next 25 hours,

I do not have to think about doing anything, creating, or decon-

structing. All is perfect as is. I can just be and reconnect with

myself and my Maker.

3 6

S H A B B A T, C H A L L A H & W O M A N

All week, we are busy doing and creating but, while doing so,

we are not entirely connected to who we are at our essence. Our

workweek reality labels us in terms of what we do: “I’m a doctor,

teacher, etc.,” or, in terms of our relationships, “I’m her mother,

his daughter, her sister . . . .” All of these terms describe us in

relation to things that are outside of us and we sometimes lose

ourselves in these descriptions. We think we really are a doctor

or a wife and this becomes our definition. We reject the whole-

ness of our inner selves and forget that, aside from all descrip-

tions, we are the essential soul we were born with and will own

for the rest of our lives.

On Shabbat, we return to our essential selves. The fact that we

cannot create anything new on Sh

abbat means that we, and the

world, have the permission to simply exist, exactly as we are, for

this one day of the week.

What a relief!

When we take six strands of dough that we created with our

own hands and braid them together, we are bringing together

the six days of the week—of working and striving and creating—

and gathering them into one perfect whole, the day of Shabbat.

The many restrictions of Shabbat that, to a child or newcomer

to the tradition, seem to be a series of “nos,” actually create an

oasis. It’s never about the “no”; it’s about the space that is creat-

ed when all that other stuff is removed.

In college, while studying communication design, the Drawing

101 instructor began the very first class by telling us that we

were going to learn a new way of seeing. We were given pencils

and papers and instructions to sit in a circle around the center

of the room, which contained nothing but a chair. The instructor

told us not to look at the chair itself; we could only draw the

3 7

R I S I N G

“negative space” around the chair. Lo and behold, while focus-

ing on the negative space, the perfect shape of a chair emerged.

Turns out, it had never been about the negative space; it had

been about how to find the shape that was formed within it.

Such is the day of Shabbat: a series of restrictions and fences,

creating a perfect oasis in time.

Shabbat and Challah

During their forty years of desert wanderings, the Jewish peo-

ple were deeply aware of the Source of their sustenance. Each

morning, they awoke and found a fresh layer of manna, heav-

en-sent bread, a perfect nutrient source, protected by dew and

ready to nourish and sustain them. Each day, exactly enough

manna for that day would fall, compelling a tremendous trust in

the continuous flow of their life-sustaining food. Only on Friday

was an extra measure of manna given and collected, eliminating

the need to gather on Shabbat. As such, manna became the sym-

bol of our connection and gratitude to the ultimate Source of all

our sustenance.

The two challahs on our Shabbat table symbolize the double

portion of manna, the original Shabbat bread, and are powerful

reminders of the bond of trust and gratitude that lies at the very

essence of this day. When we separate this day of the week –

Shabbat – and use it to reconnect with the Source of all the gifts

we received during the week, we remember that we, too, stem

from this Source.

The sanctification of one day of the week is much like the re-

moval of the piece of challah. We declare that this day, and this

piece of dough, is separated and holy. And it reminds us that all

3 8

S H A B B A T, C H A L L A H & W O M A N

the other dough, and all days of the week, are sourced in holi-

ness, as well.

Just as the separated ounce of challah reminds us of the high-

er origin of all our bread and nourishment, Shabbat is a deep

declaration of trust and gratitude in our Source of sustenance as

something beyond us and bigger than us. While we need to put

ourselves out there and make a vessel for sustenance to come

in, we always need to remember that, ultimately, our livelihood

is not in our control. The sustenance we receive is a Divine gift.

And our abstention from work on Shabbat is the ultimate state-

ment of reliance upon and thankfulness for it.

Shabbat and Woman

Shabbat is always referred to in the feminine sense: Shabbat

Hamalka/ Shabbat the queen. Its energy is visually represented

by the image of a queen, and the energy of the day of Shabbat

is that of malchut/royalty or receptivity. It is the vessel that re-

ceives all energy from the previous week and is impregnated

with the possibilities of the week to come. Shabbat and challah

and the woman all embody the qualities of receiving and grati-

tude.

We are taking off a piece of our basic nutrient staple, the dough

for the bread with which we intend to feed our family, implying

an awareness that the source of this sustenance transcends our

efforts. As such, the separation of challah represents implicit

trust and gratitude, gratitude being the capacity to acknowledge

the source of our gifts and express thankfulness for them. These

are both inherently feminine characteristics as outlined in Kab-

balistic teachings.

3 9

R I S I N G

An important note to my readers: Throughout this book, when

speaking of masculine and feminine energies as outlined and

depicted in Kabbalistic teachings, I am not speaking exclusively

of either a man or a woman. The Torah acknowledges that man

and woman each contain both energies within them: “[Z]achar

u-nekeiva bara otam/[M]ale and female He created them” (Bere-

ishit 1:27).

Masculine and feminine energies working in tandem enliven

each of us, to a lesser or greater degree. However, “woman” be-

comes a prototype of female energy, and this is reflected in her

biological makeup, as well. The same for “man” with male ener-

gy and male biology.

Woman and Challah

Our first pronouncement upon awakening each day is one of

gratitude to our Creator for giving us a new day, expressed in the

short prayer beginning with the words “Modeh ani lefanecha/ I

am grateful before You.” These three words of gratitude have a

combined numerical value of 306, equal to the numerical value

of the word isha/woman.

In the Hebrew alphabet, some letters are energetically mascu-

line and some are feminine. The letter Hei [v], which transforms

daily lechem into challah, is a feminine letter that represents

gratitude and receptivity. It is also the letter that changes the

word ish [aht]/man to isha[vat]/woman.

Hei is the letter of creation and creativity, a function that both

receives and gives forth. It is an ability to receive in a way that is

also giving, much as the woman who receives the initial seed of

life is able to actualize it and bring forth a living being.

4 0

S H A B B A T, C H A L L A H & W O M A N

“The man brings the wheat home, but does he chew wheat? He

brings in the flax, but can he wear flax?” (Talmud, Yevamot 63a).

The woman is the one who takes the raw materials of life and

makes them nourishing, comforting, and life-sustaining. The fe-

male aspect of receptivity is not a passive pose; it is proactive

and productive.

The idea of receiving as the deepest form of giving is some-

thing that we have hopefully each experienced at some point in

our lives. On a very practical level, there are those who are able

to receive what we give them—be it an expression of our emo-

tions towards them or a physical gift—in a manner that makes

us feel like we are the ones who have been given something.

Letting Go a Little

The letter Hei is fascina

ting in that it is both silent and vocal.

It is used at the end of a word as a silent, supporting letter, and

in the beginning or center of a word as a vocal, expressive letter.

The Hei’s dual functions serve as a great lesson in creativity

and receptivity.

To truly create, we need to be present—the fullness of our

whole self must come forth—but we must also step aside to

allow for the creation to occur. The combination of full expres-

sion coupled with complete humility allows for a new entity to

emerge.

As a professional artist, I have often puzzled over the elusive

creative process, which I must access each day to do my job as

a designer, artist, and writer. It occurred to me quite early in my

career as a graphic artist that the more my ego was attached to

4 1

R I S I N G

the project at hand, the more difficulty I would have accessing

my creativity. If I was worrying about how the client was going

to like the finished piece, or whether it would appear that I was

an accomplished artist (yay!) or a fraudulent wannabe (oops!),

I would get stuck and be unable to create something “fresh.” It

was only after letting go of my attachment to the outcome and

allowing the ideas to flow through me that I could truly be cre-

ative. Of course, this flow was occurring after years of training

and on-the-job experience, all of which were very much a part of

me, but, at the moment of creation, there was no expression of

that, just a removal of ego from the story.

I have often seen this and I’m sure you must have have, also:

a couple tries so hard to conceive a child, to no avail, only to

suddenly find themselves pregnant after taking a break from

“trying” or once they’ve decided to adopt. What has happened?

Quite simply, they have removed their attachment to the out-

come from the process and made room for creation to occur.

Our forefather Avraham and foremother Sarah were childless

and unable to conceive until G-d gifted them each with the letter

Hei. Avram became Avraham, with the expressive and vocal Hei,

while Sarai became Sarah, with the silent Hei. It was then that

the creation of a child was possible.

The woman, the challah, and Shabbat are all expressions of

the silent Hei of creation, the quality of gratitude and receptivity.

The receiving is so powerful and fully absorbed that it brings

The Rising Life

The Rising Life