- Home

- Rochie Pinson

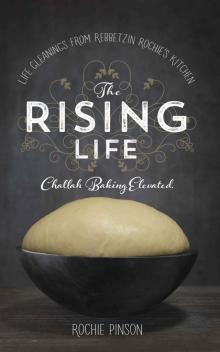

The Rising Life Page 12

The Rising Life Read online

Page 12

1 4 7

R I S I N G

Covering the Challah

Across all communities and traditions, there is a custom to

cover the challah on the Shabbat table before kiddush is recited.

The simple explanation for this custom is that we don’t wish to

shame the challah by giving the kiddush wine precedence in its

presence. In Jewish tradition, bread takes precedence over all

other foods, even wine.3 However, on Shabbat we recite kiddush

over wine before making the blessing on the challah. As such,

the challah is covered so as not to cause it the pain of embarrass-

ment.4 This is meant to be a tremendous lesson in sensitivity for

us at the Shabbat table. If we are so careful not to embarrass a

loaf of bread, how careful must we be with the feelings of those

surrounding us at our table.

There is also a tradition for the challah to be set between

two protective layers—a covering on top of them and a cloth or

board beneath them—representing the two layers of dew, one

above and one below, that protected the manna. 5

lah should be cut first, since the bottom challah represents the feminine and on

Shabbat eve, Shabbat is referred to as “Shabbat Queen” (Orach Chaim 274:1

Magen Avraham.) . This is consistent with Kabbalistic tradition. Others write to

cut the top challah first on Friday night (Kol Bo, Mitzvah 24).

3 Jewish law stipulates that the blessing over bread is always to be recited first and in favor of the blessings over all the other foods to be eaten at the same

meal.

4 Tur, Orach Chaim 271

5 Tosefos, Pesachim 100b. Taz, Orach Chaim 271:12

1 4 8

C H A L L A H C U S T O M S & S E G U L O T

CHALLAH SEGULOT

• Separating the challah is a powerful time for per-

sonal prayer. The name Chana is commonly taught

as an acronym for the three special mitzvot of wom-

en: challah, niddah/family purity, and hadlakat

hanerot/Shabbat candles.

Historically, Chana was the antecessor of the system of

prayer as we know it today, representing effective communi-

cation with the Divine. Through the three mitzvot that make

up her name—separating challah, renewing ourselves in the

mikvah, and lighting Shabbat candles to illuminate our en-

vironment—we are able to similarly connect and communi-

cate with our higher selves and our Source.

• The following custom has recently become common among

Jewish communities: Forty6 women devote their prayers

while separating challah to the merit of a person in need of

salvation (such as recovery from illness, a worthy mate, or

the birth of a child). Some say this should be done with a

group of 43 women.7

• The mitzvah of separating challah is recognized as a segulah

for an easy, safe birth. It is customary for a woman to sepa-

rate challah at least once in the ninth month of pregnancy.8

6 The number 40 is significant in terms of radical change from one capacity to

another, such as the 40 se’ah measurement required for a mikvah, the body

of water that transitions a person from one state of being into another, to be

kosher.

7 The number 43 is the numeric value of the word challah. It is also the numeric value of the word gam (also), indicating a completion and inclusion. As such, it

is a very significant number in terms of finding one’s soul-mate.

8 Mishna Shabbat 2:6- Women may be judged during childbirth according to

their observance of the three mitzvot of women.

1 4 9

R I S I N G

• According to our sages, the mitzvah of separating challah

brings a blessing for prosperous livelihood into the home.

“You shall give the first yield of your dough to the kohen to

make a blessing rest upon your home” (Yechezkel 44:30).

An early German and Central European name for challah was

barches, an acronym for the phrase “Birkat Hashem hee taa-

sheer/Hashem’s blessing brings riches” (Mishlei 10:22).

Another name for challah that relates to this verse, used in

the same part of the world, is dacher.

• Schlissel Challah: A very popular tradition related to chal-

lah, this takes place only once a year, on the first Shabbat

immediately following Passover. It is a tradition that relates

to sustenance and there are various explanations given as to

why this is done. The name given to this tradition is “Schlissel

Challah,” or “Key Challah” and the custom is to either bake

a key into the challah, make a key shape with dough on top

of the challah, and some even form the entire challah in the

shape of the key. The premise of this custom is that this par-

ticular Shabbat is an auspicious time for sustenance prayers,

and the key on or in the challah represents the opening of

the gates of sustenance for the coming year.9

9 The earliest recorded source for this custom seems to be the sefer Oheiv Yisrael

by Rabbi Avraham Yehoshua Heshel, the Apter Rav. He refers to the custom of

schlissel challah as “an ancient custom,” and offers numerous Kabbalistic in-

terpretations for this custom. The Apter Rav writes that after forty years in the

desert, the Jewish nation continued to eat the manna until the first Passover in

the Land of Israel. They brought the Omer offering on the second day of Pass-

over and from that day on, they no longer ate manna, but food that had grown

in the Land of Israel. Since this time of year is when they began to concern

themselves over their sustenance rather than having it fall from the sky each

morning, the key on the challah is a form of prayer to G-d to open up the gates

of livelihood.

Another source for this custom is from the second mishnah in tractate Rosh 1 5 0

C H A L L A H C U S T O M S & S E G U L O T

• Because of the tremendous zechut/merit that is attributed

to the mitzvah of separating challah, it is recommended to

bake challah, primarily for the purpose of fulfilling this mitz-

vah, at least once a year. Ideally, one should separate challah

during the Ten Days of Repentance.10

• Our sages instituted that we perform the mitzvah of ha-

frashat challah outside of the Land of Israel so that we do

not forget “the Torah of challah.”11 It follows, therefore, that

performing the mitzvah of challah is a special segulah for re-

membering and improving memory.

• Challah is a special segulah for teshuvah in general and, even

more specifically, for the baal teshuvah/returnee or a con-

vert to Judaism.

This is because even wheat that was imported into the Land

of Israel was considered to be wheat of the Holy Land. There-

fore, we were required to take challah from it even at the time

when challah was only separated from wheat of the Land of

Israel. This is indicative of the possibility and the power of

Hashanah, which says that on Pesach we are judged on the grains, represent-

ing parnasah/livelihood. Rabbeinu Nissim asks, “If we are judged on Rosh Ha-

shanah how are we then judged on Pesach?” He answers that on Pesach it is

; determined how much grain the world will have during the coming year, but

on Rosh Hashanah it is decided how much of that grain each individual will

receive.

The Meiri, however, says that on Rosh Hashanah it is decided whether one will live or die, suffer or live in peace, etc., but that Pesach is when we are judged

with regard to the grains. Based on this there are a number of customs that are

practiced by Sephardic communities on the night that Pesach ends, signifying

our desire to be granted ample sustenance. In Syria and Turkey they would put

wheat kernels in all four corners of the house as a sign of prosperity for the

coming year (Moed L’kol Chai, Beis Habechirah, R’ Chaim Palagi).

10 Siddur Kol Eliyahu

11 Rambam, Hilchos Bikurim, 5:7

1 5 1

R I S I N G

change and return.12

Another connection of challah to teshuvah is that the process

of the mitzvah of challah is three-fold, which connects to the

three phases of teshuva as defined by the Baal Shem Tov13:

submission, separation, and sweetening. Submission is the

acknowledgment that the dough, seemingly whole and com-

plete, is imperfect without the removal of a piece. Separation

relates to the actual separation of the piece of dough for the

mitzvah and the sweetening is the eating and enjoyment of

the completed challah.

• The initial shattering in creation occurred from a sense of “I

will rule,” the serpent’s claim that with the eating of the for-

bidden fruit, Eve and Adam would be like G-d Himself. The

rectification of this breaking, the tikkun or healing of the

world as it were, will come from humility and gratitude, both

primary factors in the mitzvah of challah. As such, the sepa-

ration of challah is a segulah for the healing of our emotional

sefirot and, indeed, a healing for the original shattering of the

first human, Adam, who was called “challato shel olam/ the

challah of the world” (Bereishit Rabbah 14:1).

12 In Challah 2:1 it says that we learn this from the word “shamah/there” in Bamidbar, 15:18: “Speak to the children of Israel and you shall say to them, ‘When

you arrive in the Land to which I am bringing you shamah/there.’”

13 Rabbi Yisrael ben Eliezer, known as the Baal Shem Tov, (d.1760), is the founder of the Chasidic movement.

1 5 2

Chapter IX

Challah Meditations

1 5 3

R I S I N G

Forming the Dough

: meditations on the ingredients

Challah is not just a recipe for bread; it is intrinsically a recipe

for life itself. Each of the five primary ingredients reflects an es-

sential aspect of life and the nurturing of it.

As we add each ingredient, we become present to the deeper

significance of that particular element and allow ourselves to be

fully and joyfully in the moment. The challah dough that results

is a direct reflection of our intention.

WATER

In the beginning, there was only water. All life emerged from

water, water flows from Eden into the world, water breaks and

we emerge.

Water, as a primordial element and a life-giving force that con-

tinually flows from higher ground to lower places, represents

the very essence of life – that part of us that is eternally linked to

the Source of all life, namely, our soul.

As we begin the creation of the dough with the pouring of

water, we remember that the essence of who we are, and the

essential core of those we love, is a precious fragment of the Di-

vine. We, and all of humanity and creation, in fact, are a direct re-

flection of G-dliness and, as such, we are pure light and goodness

at our core. This reminds us of our own inherent worthiness and

the innate beauty of those we care for. We begin nurturing with

the realization of all of creation’s innate holiness and value.

1 5 4

C H A L L A H M E D I T A T I O N S

YEAST

We sprinkle in the yeast and reflect upon the fact that this

is the ingredient that inflates the challah. This represents the

self-esteem, confidence, and reassurance we can give in abun-

dance to those whose lives we directly influence. We can even

continually grant small measures of it to each person whose

path we cross during our lifetime. The balance of the yeast is

crucial to the growth of the dough; we are aiming for a healthy

and perfect rising.

SUGAR

Sugar is about creating a sweet environment. While adding

sugar, we think about how we can continue injecting chesed,

kindness, and sweetness into our home in a way that encour-

ages growth and movement. Sweetness is essential in the be-

ginning of life and throughout life, in fact, and should be used in

abundance. That said, just as sugar causes the yeast to activate

when used in the right proportions, the tendency of sugar is also

to create an overgrowth if applied without restraint or boundar-

ies. And that is where the salt, or gevurah, comes into play. More

on that soon . . . .

FLOUR

Flour is the main substantial ingredient of bread, which is

known as the “staff of life.” It represents the physical body and

health of our family and of humanity. We need to ensure that

1 5 5

R I S I N G

our physical vessel is being properly cared for so that we can ac-

cess our higher self. “[I]m ein kemach, ein Torah/[W]ithout flour

there is no Torah.” When pouring the flour, we meditate on the

physical health of those in our care, and pray for their well-being

and for the healing of all of humanity.

SALT

Now we can measure in the salt. Salt represents gevurah,

boundaries and discipline. When added in correct proportion,

salt provides necessary structure to the dough and highlights

the sweetness of the challah. Too much salt, however, is harsh

and destructive. As we add in the carefully measured amount of

salt, we meditate on our gevurah approach with our family and

all those we come in contact with. Remember that we add the

salt only once the sugar has done its work! Sweetness before

harshness always, and always a higher proportion of sugar to

salt.

EGGS and OIL

Eggs are a binding ingredient. Conversely, oil is an element

that stands apart.

When opening and adding the eggs, we reflect on the elements

of similarity that connect us with our families and the numerous

factors that remind us of our overall shared humanity. In this

way, we draw together and feel accepted, loved, and connected.

While pouring in the oil, we notice how the substance stub-

bornly resists the melding process, and remember that those

1 5 6

C H A L L A H M E D I T A T I O N S

things that make us stand apart are the very same qualities that

make us singular and valuable. In all the ways our loved ones

are different from us and each other, they are unique and cho-

sen. We meditate on the oil and remember to cherish the unique

VANILLA

This intention is for any added ingredient that we put into our

challah just because we like it. When we sprinkle in the flavor

of our choice—sweet, savory, or otherwise—we consider the

ways in which we nurture that are singular to our personality

and life experience. We remember that the best nourishment is

the one that comes from an open, honest, and giving place, and

we strengthen our resolve to continue nurturing from that place

within ourselves.

Meditation While Mixing

The work we do as nurturers, often physical and at times

monotonous, is really so much more than meets the eye. In the

work we do with our hands, we have the power to inject love

and kindness into the hearts of our family and all those around

us.

Nurturing and bringing to life is an innately feminine trait

that stems from the quality of malchut. As receivers, we are con-

stantly downloading energy and have it within us to transform

and infuse those energies into life-giving ingredients, bringing

them together to sustain and elevate the lives of those we love.

1 5 7

R I S I N G

The act of taking challah is, in and of itself, a great mitzvah.

It is a declaration of trust in the sustenance of Hashem and the

belief that all we have and all that we are is, in actuality, a direct

manifestation of Divine. By extension, the entire process of bak-

ing challah becomes an experience of connectivity to G-d and to

all of humanity.

Bread is the very essence of sustenance. By baking bread, we

are offering life and health to those we love. By putting our de-

votion and mindfulness into the dough, we are offering spiritual

and emotional sustenance, as well.

We remember to remain connected and present during the

process, appreciating the fact that by bringing all of ourselves

into this moment, we are giving the very best of who we are to

the ones who need it the most.

Kneading Meditation I

: teshuvah meditation

Hachna’ah, Havdalah & Hamtakah /

Submission, Separation & Sweetening

This is an especially appropriate meditation for the months of

Elul and Tishrei, and particularly during the 10 days between Rosh

Hashanah and Yom Kippur, known as the Aseret Y’mei Teshuvah /

the Ten Days of Repentance. If a woman doesn’t usually bake chal-

The Rising Life

The Rising Life